Octobrer 2024

As a preamble to this opinion, the Conseil de l’Éthique Publicitaire [Advertising Ethics Council] would like to pay tribute to Lucas Boudet, Director General of the European Advertising Standards Alliance (1978-2024). His kindness, availability and knowledge fuelled our discussions. Without these many rich discussions, this opinion would not be what it is.

“Thinking is comparing” [1] [2]

Comparing means drawing parallels between elements in order to identify similarities and differences. In the case of advertising self-regulation, a comparison between the various European countries shows that it is generally recognised as being effective, rapid and less costly for taxpayers than traditional litigation before the courts.

To shed light on the ARPP and consider the future of advertising self-regulation, we need to look at what sets us apart and what brings us closer to other countries. This leads us to ask: is there a desire for greater regulation and/or self-regulation at European level? Who wants this and why? Is it feasible? What would be the advantages? What would be the limits? This also raises the question of how far self-regulation is ahead of the law: is the law catching up with self-discipline? Is self-regulation proof of openness? Does it reflect public debate? What are the weak signals?

In this opinion entitled « Europe, advertising self-regulation and cultural diversity », we first set out the framework for self-regulation at international level and provide an overview of the situation at European level (part 1). We then examine the desire to establish common regulation and self-regulation at European level (part 2). We then question the possibility of a uniform approach that takes account of cultural diversity in Europe (part 3). Finally, we conclude by formulating recommendations (part 4).

It is important to specify that the figures, data and information presented are provided for information purposes only to help understand the situation and in no way convey a value judgement.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1/ A common framework, a shared commitment

1.1./ The International Chamber of Commerce’s Advertising and Marketing Communications Code

1.2./ Self-regulation encouraged by Europe

1.3./ The European Advertising Standards Alliance: a response to European demand

1.4./ A wide variety of sizes and sources of funding

1.5./ A variety of juries

1.6./ The power of European juries

2/ Regulation, self-regulation: is there a desire for harmonisation at European level?

2.1./ National regulations and advertising

2.2./ A trend towards greater regulation?

2.3./ Who is in favour of supranational regulation and self-regulation?

2.2.1/ International brands

2.2.2./ Digital players

2.2.3./ Public authorities?

2.4./ Critics of self-regulation, advocates of more regulation

2.5./ Will self-regulation soon be overtaken by regulation?

3/ (In)compatibility between a uniform approach and cultural diversity?

3.1./ Different volumes of complaints in different countries

3.2./ Grounds for complaints and national public debates

3.3./ Convergence and divergence on complaints

4./ Conclusion and recommendations

1/ A common framework, a shared commitment

In this first part, we examine the international framework of self-regulation in order to understand its foundations, established by the International Chamber of Commerce. We then focus on Europe, which is driven by a political desire for unity and has encouraged the creation of the European Advertising Standards Alliance (EASA). Finally, we will compare the structures of the members of this alliance, considering their human and financial resources and the power of their juries.

1.1./ The International Chamber of Commerce’s Advertising and Marketing Communications Code

The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) represents more than 45 million companies from all sectors of the economy in over 170 countries. Its mission is to promote international trade and investment, and to help businesses meet the challenges and seize the opportunities of globalisation. The International Chamber of Commerce has consultative status with the United Nations. Its activities focus mainly on three areas: general policy, the development of trade rules and the resolution of disputes. Its rules are based exclusively on the principle of self-discipline.

In 1937, the International Chamber of Commerce drew up the « Code of Advertising Practice » – often referred to as the « ICC Code » – a set of rules which constitute the benchmark for professional self-regulation in advertising. This code is of great value because of its historical and worldwide character, and because the International Chamber of Commerce is recognised beyond the advertising field: it is an authority. The ICC Code defines a common framework and lays down universal foundations. Since its creation, the spirit of the ICC Code has been based on its first article, which states that advertising must be legal, truthful, honest, decent and socially responsible. These are therefore global rules of conduct for responsible communication.

The eleventh update of the ICC Code was formally adopted by the ICC bodies in June 2024 and officially launched on 19 September 2024.

At European level, all self-regulatory bodies apply the principles of the ICC Code. However, usage and interpretation may vary from country to country. Finland, Sweden and Belgium apply the ICC Code directly as such, simply by translating it into the national language. Greece and Turkey apply it with certain modifications linked to their legal framework. It is the case law which will interpret the provisions of the Code, whether strictly or not. In Sweden, for example, the interpretation of the general rules allows for strict treatment of environmental claims. In most other European countries, the principles of the ICC Code serve as inspiration. These countries interpret the Code according to their culture and adapt it to their national context by drafting national Codes or specific recommendations. With regard to the relationship between the ICC Code and national codes, a parallel can be drawn with European directives, which are transposed at national level. The ICC Code is sometimes criticised for being too general in relation to legislation in Europe, but it should be borne in mind that this Code is intended to apply worldwide, where the latitude left by the various national legal frameworks varies greatly. Presenting general principles is intentional; it facilitates adaptation to national or regional cultures as well as to changes in practices and techniques.

In addition, the ICC Code is very useful for the development of a self-regulatory system in countries that do not yet have one. When a new self-regulatory body is launched, it often starts by using the ICC Code, which can be applied directly. Then, gradually, the body develops specific rules, often empirically, to meet particular needs. When these specific rules multiply, the organization consolidates them all in a single document: its own code. In short, the ICC Code is the lowest common denominator of the various self-regulation systems in Europe.

1.2./ Self-regulation encouraged by Europe

In Europe, since the 1980s, European governments have promoted ‘soft law’ approaches, such as codes of conduct and guidelines, favouring self-regulation and co-regulation[3] . In 2001, the European Commission published a White Paper promoting co-regulatory mechanisms, and the European Council commissioned the Mandelkern expert group[4] to propose an action plan for better regulation. This report considers self-regulation as an alternative to regulation. Another report, published by the Directorate-General for Health and Consumer Protection under the direction of Robert Madelin, gave significant political support to the recognition of self-regulation in advertising. Since then, self-regulation has been recognised in several EU directives, notably on advertising, unfair commercial practices and audiovisual media services. In addition, the European Commission recognises self-regulation and co-regulation in its Better Regulation Toolkit[5] , the latest iteration of which dates from 2023. In addition, the European Economic and Social Committee published an opinion in 2015 recommending that self-regulation and co-regulation should be considered as important instruments for supplementing or reinforcing hard law.

1.3./ The European Advertising Standards Alliance: a response to European demand

The creation of the single European market[6] brought with it the need to protect European consumers across national borders and to manage cross-border complaints. It was against this backdrop that the European Advertising Standards Alliance (EASA) was set up in 1992 by the industry, positioning self-regulation as a response to this new challenge. The European Advertising Standards Alliance promotes ethical rules for commercial communication, while respecting cultural diversity and national regulations. EASA promotes and defends advertising self-regulation; it leads and coordinates a network of national self-regulatory bodies.

The Alliance issues recommendations and facilitates the exchange of best practice. It also coordinates cross-border complaints.

The European Advertising Standards Alliance

The European Advertising Standards Alliance brings together 28 advertising self-regulatory organisations covering 26 countries.

The Alliance’s objectives include the following:

- To promote responsible advertising through effective self-regulation by providing detailed guidance for the development and implementation of advertising self-regulation in the interests of consumers and businesses.

- Establish high operational standards for advertising self-discipline systems.

- To provide a space for the advertising ecosystem to work together at a European and international level to address common challenges and ensure that advertising standards are fit for the future.

The Bluebook

In the Bluebook, the European Advertising Standards Alliance presents the organisation of each of its 28 members according to the following criteria:

- Structure, composition and financing

- Status and structure of the self-regulatory organisation

- Responsibilities of the self-regulatory organisation

- Mandate of the self-regulatory organisation

- Political and legal recognition

- Membership and financing

- Activities of the self-regulatory organisation

- Communication

- Training and education

- Advice for all media and TV pre-broadcast advice

- Follow-up

- Complaints handling and mediation

- Penalties

- Complaints handling roadmap

- Codes and rules

- Overview

- Rules covered by the code

- Codes and self-regulation rules specific to a product or sector

- Validation of the charter

- Best practice implementation scorecard

- Implementation of the ICC framework

- Hot news

www.easa-alliance.org/publication/blue-book/

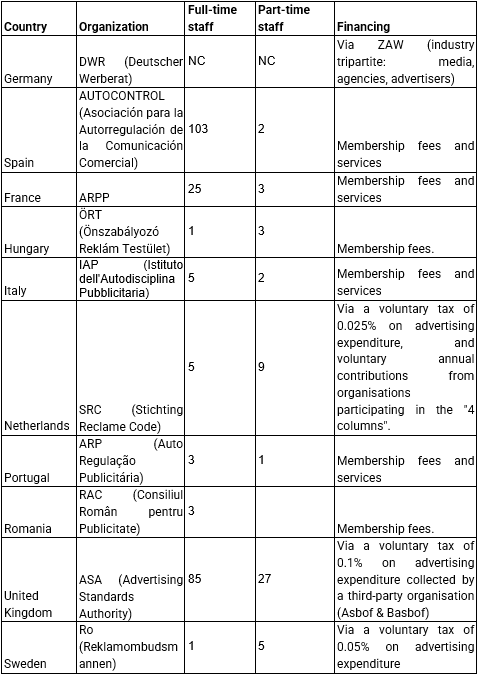

1.4./ A wide variety of sizes and sources of funding

The staffing levels of the self-regulatory bodies illustrate these disparities: some have only one or two employees, while others employ several dozen. One might hypothesise that this has consequences for their ability to absorb a greater or lesser volume of complaints, which in turn could depend on the size of the market concerned – the number of complaints could also depend on the obligation (or not) to give prior notice. However, a small number of staff could also be interpreted as a sign of efficiency. The EPC does not favour any of these hypotheses, which are a matter for national inter-professional governance decisions. The difference in size could also explain the innovation of some bodies, which are almost exclusively involved in handling complaints, and are mainly involved in preventive action, prior to dissemination. Those with larger teams have the means to proactively launch projects that go beyond day-to-day management, for example by participating in working groups and think tanks organised by third parties, anticipating the creation of rules and optimising the management of consumer complaints. ARPP has innovated by using artificial intelligence for image recognition to speed up the investigation of non-compliance. France presented the first AI use cases to the European Advertising Standards Alliance network in 2018, followed by the UK and the Netherlands. Thirteen countries are now using computer technologies to analyse online advertising on a large scale. For its part, the Spanish organisation Autocontrol has developed « cookie advice« , a voluntary pre-release advice on the use of cookies and data for advertising. Here, the issue is to address the ethical use of data for advertising targeting, in compliance with European rules, in particular the RGPD. This approach has not been adopted in some other countries due to the local context: for example, in France, the subject is largely managed by the CNIL, an independent administrative authority.

In terms of funding, most European self-regulatory bodies rely on membership and pre-release advice. However, in the UK, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden and Greece, funding is based on a different system, commonly known as the « levy« . This is a levy charged by the agencies on top of their rates, which is paid back to the local self-regulation system. This system generates much higher revenues for some of these agencies than for others. In some countries, companies are also charged procedural fees. In Portugal, for example, a company that is a member of self-regulation and wishes to challenge a competitor’s advertisement must pay €850. This funding enables the organisation to carry out in-depth investigations.

This raises questions about how self-regulatory bodies are funded. However, this question must be subordinated to another: do the self-regulatory organisations need more funding? And if so, to meet what needs? To date, professionals seem satisfied with the way their organisations operate.

In any case, a comparison of European self-regulatory bodies must be assessed in the light of the human and financial resources that each country devotes to them, which determines their proactivity and the visibility of their actions.

Membership and funding of self-regulatory bodies

To make it easier to understand the situation, we have limited ourselves to presenting data from around ten representative organisations in Northern, Southern, Eastern and Western Europe.

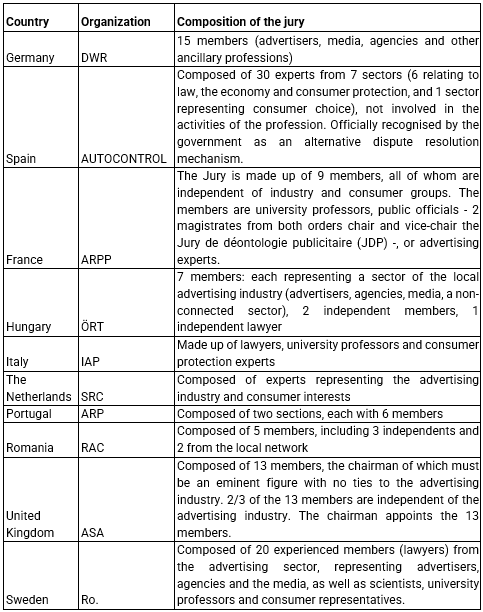

1.5./ A variety of juries

The question of the composition of juries is particularly interesting, as they do not always bring together the same stakeholders. In some countries, juries include industry representatives, while in others, such as Spain, France and Italy, this is not the case. Some juries also include consumer representatives, as in Spain, the Netherlands and Sweden. The absence of consumer representatives on some juries could be a legitimate criticism and raises questions about the openness of juries to representation from consumers and the voluntary sector.

Composition of juries

The CEP noted that appeals are not allowed in all countries. For example, it is possible in Germany (before the courts) and Sweden, but not in Italy and Portugal. In the United Kingdom, as in France, it is subject to analysis by the Advertising Standards Reviewer.

The CEP also noted the existence of a mediation service in Portugal and the United Kingdom. If the parties reach an agreement with the help of the panel, the panel does not issue an opinion. Thus, if an advertiser undertakes to modify an advertisement and its competitor undertakes to withdraw its complaint, then there is no publication. This mediation system is similar to the French « Réglement amiable »[7] , which is often proposed by the chairmen of the Jury de Déontologie Publicitaire, but rarely accepted by the complainants.

1.6./ The power of European juries

Although most sanctions are based on the principle of « name and shame« , some juries seem to have a greater capacity to exert pressure than the French Jury de Déontologie Publicitaire (JDP), even though the ARPP’s statutes provide its governance with similar means of action.

- In the UK, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) can issue warning notices to media publishers so that advertisements in breach of the codes are not shown. The ASA can also have an advertiser’s paid search ads removed when an ad on Google is in breach of the code. The ASA keeps a list of advertisers who tend to run too many ads that are considered misleading on their websites, as well as a list of content creators who do not comply with the Code (which can influence the choice of content creators by agencies and advertisers). France takes a different approach, rewarding content creators who behave well with the « Responsible Influence Certificate »[8] .

- In Germany, the Deutscher Werberat can request that the broadcasting of an advertisement in breach of the code be halted. This power is based on the principle that advertisers who are members of the self-regulatory body agree to abide by the panel’s decisions. If the advertiser does not stop the broadcast of an advertisement for which the complaint is well-founded, the Deutscher Werberat may issue a reprimand, which it makes public.

- In Italy, the Istituto dell’Autodisciplina Pubblicitaria can order an advertiser to end an advertising campaign within a binding deadline, and all media are required to comply with this decision. In the event of non-compliance, notification of the behaviour may be published in the media deemed appropriate by the authority.

- In Hungary, failure to comply with the Jury’s decision may result in the advertiser’s membership of the Önszabályozó Reklám Testület being terminated. In France, termination of the membership of a member who does not comply with a decision of the JDP must be approved by the ARPP Board of Directors.

A study of the framework reveals a historical desire to promote self-regulation at the level of each European country. However, there are major structural and operational differences between the various self-regulatory bodies. The question that arises is whether there is a will to go further by strengthening common self-regulation, or even by strengthening the legislation itself.

2/ Regulation, self-regulation: is there a desire for harmonisation at European level?

In this second part, we begin by examining national regulations. Then we ask: is there a trend towards more regulation, and who are the proponents? Finally, we examine the relationship between self-regulation and regulation.

2.1./ National regulations and advertising

In addition to the principles of self-regulation shared by all European countries, they have hard law based on very common rules. Most countries rely on the Consumer Code, regulations on unfair competition and consumer protection, and media laws. In France, the main foundation remains the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, transposed into the Consumer Code and therefore within the remit of the DGCCRF.

Some countries have specific laws on advertising, such as the « Communications Act 2003 » in the United Kingdom, the « General Advertising Act » in Spain, Act no. 147/2001 in Slovakia, which regulates the content and distribution of advertising, as well as the rights and obligations of advertisers, the « Advertising Act » in the Czech Republic, or the « Economic Advertising Act » in Hungary, which defines the basic conditions and certain restrictions on commercial advertising. In France, there is no « Code de la Publicité » (Advertising Code) among the sixty or so Codes that exist in France; on the other hand, « Articles Publicité » (Advertising Articles) appear in more general laws, such as the Loi d’Orientation des Mobilités (Mobility Orientation Law) and the Loi Climat et Résilience (Climate and Resilience Law), for example with regard to car advertising.

A majority of the sectors and subjects covered by legislative proposals in European countries are fairly widely shared. These include financial services, medicines, health products, children’s food, gambling, alcohol and content creation (influence).

In some countries, regulation is decentralised. In Spain, the seventeen autonomous communities impose specific rules on outdoor advertising. In the Netherlands, some municipalities impose local restrictions on outdoor meat advertising. The city of Edinburgh is going to ban advertising for airlines or cars with internal combustion engines.

In addition to self-regulation and regulation at national, or even local, level, the CEP wondered whether there was a willingness to regulate and/or self-regulate at European level.

2.2./ A trend towards greater regulation?

The question of the growing desire for supranational regulation raises questions about the tendency for ever greater regulation at both EU and national level. The trend towards greater regulation is persistent, supported by European institutions, national governments and various interest groups. This trend is aimed at harmonising the market, protecting consumers and addressing environmental and social concerns.

Public authorities want to be seen as responsive and relevant, even when the issues do not always require new legislation. The issues to be regulated change according to social pressures, national events or changes of government.

Conversely, there is also a desire for simplification to avoid over-regulation. The « better regulation agenda« , which has been in place for the past ten years, aims to simplify EU regulations. The President of the European Commission has reiterated these intentions, with a Vice-President in charge of simplification who will have to report annually to Parliament .[9]

In addition, there is some evidence of legislative fatigue following the completion of major regulatory frameworks such as the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the European Artificial Intelligence Act. Some Member States are now focusing on the practical application of existing regulations to ensure that they achieve the desired results rather than on the introduction of new laws.

The impression that there is a desire to strengthen regulation must therefore be qualified.

2.3./ Who is in favour of supranational regulation and self-regulation?

It is undeniable that some players want (and are actively working towards) greater regulation and/or self-regulation at European level.

2.2.1/ International brands

International brands need harmonisation of both legislative and professional regulations to simplify compliance and reduce the costs associated with international advertising campaigns. Consistent and predictable supranational regulation would, in their view, facilitate market access and encourage innovation and long-term investment. It would also boost consumer confidence, particularly in areas such as data protection, environmental sustainability and corporate responsibility. This is why many brands support global standards, such as the ICC Code, which they then adapt to local circumstances.

However, full harmonisation of regulations remains difficult to achieve, as each country can interpret and adapt European rules differently, sometimes adding further restrictions. These national adaptations can even influence the internal charters that companies impose on themselves at international level: local rules become global standards. For example, the ARPP recommendation, incorporated into the French Environment Code, states that vehicles should not be shown in natural areas; this could encourage a German manufacturer to develop a specific campaign for this market, but also to apply this constraint internationally and not just in France.

For some advertisers, compliance in France and Germany is often seen as a guarantee of compliance in other European countries, because of the strict regulations in these two countries, particularly on alcohol advertising.

Similarly, local solutions to certain problems common to several countries may be worth adopting internationally. This is the case with content creators and the Responsible Influence Certificate developed by ARPP, which is intended to become a European certificate[10] in collaboration with the European Advertising Standards Alliance. This subject is of interest to international advertisers and has, for example, been discussed at meetings of the World Federation of Advertisers (WFA).

The CEP also looked at the consequences for creativity of the diversity of self-regulation systems. Although self-regulation is often perceived as a constraint, it would appear that this does not hinder creativity, as this constraint is accepted insofar as it is co-constructed with the representatives of the advertising professions. The diversity of frameworks from one country to another forces brands to adapt their messages and strategies to meet national standards and specific cultural expectations. A common advertising concept can be adapted to suit different countries. The need to adapt to different cultural contexts often stimulates innovation and creativity.

It is in the name of freedom of expression, as well as to maintain a good level of creativity, that the rules are often formulated in a negative way (« you must not represent/say/do ») rather than a positive way (« you must represent/say/do »): what is not forbidden is allowed.

2.2.2./ Digital players

The major digital platforms, such as Meta, Google and Amazon, are strongly in favour of international harmonisation, which would give them consistency and predictability. Their policies are global, and they cannot – or do not wish to – systematically adapt them to local specificities. Moreover, the CEP noted that in Google’s report on ads blocked online, the platform does not provide detailed information by country.

However, the managers of the major digital platforms are well aware that full harmonisation is not feasible. In practice, they cannot avoid having to adapt to national legislation because of differences in both legislation and culture. This would reflect a failure to listen to local issues.

Those involved in programmatic buying, whether on the web, on social networks or now in digital signage, are also wondering what rules to adopt. How do you self-regulate content that a medium receives a few seconds before it is broadcast? The challenge of real-time seems to require the implementation of technological tools to accept or reject the display of a campaign. The complexity lies in identifying problematic visuals and redirecting them, not to the screen, but to a validation channel. This raises the question of a paradigm shift from ex-post control to ex-ante control.

Thirteen European self-regulatory bodies are using artificial intelligence to analyse advertisements on a large scale before they are broadcast, but this poses challenges in terms of the perception of the role of self-regulation and a priori or a posteriori judgement.

Google also makes efforts to verify advertisements before they are shown, by removing or restricting them. However, Google does this mainly on legal grounds (fraudulent ads, illegal products, etc.) and not by virtue of the self-regulatory code in force in the country of distribution. The complexity of using artificial intelligence to deal with breaches of each self-regulatory body’s code stems from the fact that each country has its own rules and, above all, different cultures, which may or may not accept certain practices or wording.

The main risk of automation, whether by self-regulatory bodies or platforms, is finding the right balance: too many restrictions could censor acceptable content, while too few could let inappropriate content through, leading to frustration on the part of advertisers in one case or consumers and public regulators in the other.

2.2.3./ Public authorities?

The European Commission and the European Parliament, within the limits of their prerogatives and in compliance with the principle of subsidiarity, support the harmonisation of regulations to promote market integration and guarantee high standards in all Member States.

The Commission is made up of experts responsible for implementing the strategic orientations of the mandate. These experts are supposed to be able to listen to all the stakeholders, decipher the messages and assign a weighting factor to each voice in order to find a median solution. In this way, they can filter out the pressure exerted by the detractors of self-regulation. Within the Commission, it is important that the General Directorates concerned are well informed about advertising self-regulation practices.

Parliament is more fragmented, with varying positions of principle. Some are opposed to self-regulation, while others are pro-business and in favour of self-regulation. The discussions of the European Advertising Standards Alliance take place in Parliament with rapporteurs, co-rapporteurs and shadow rapporteurs from the other parties (they may also come from the majority party). It is a democratic process with clear-cut positions.

At national level, some government authorities see self-regulation as part of the solution to promoting responsible advertising, while others see it as insufficient (without, however, evaluating it and seeing it as a factor in problems). Depending on the culture, sometimes the public and private stakeholders can maintain an ongoing, peaceful dialogue in order to move forward; sometimes the relationship is more conflictual. On the whole, self-regulatory bodies claim to have close and positive relations with government authorities.

In the UK, Ireland and Spain, public authorities delegate part of their workload to self-regulatory bodies. In the UK, these bodies enjoy a high public profile, which is not always the case elsewhere. A recent study in England tends to show that the better known the self-regulatory body, the greater the confidence in advertising. People who have seen the Advertising Standards Authority campaign are twice as likely to trust advertising and the advertising industry.

The CEP questions the need for work to strengthen the recognition of self-regulatory bodies by the general public, in order to consolidate the confidence of public authorities and civil society.

2.4./ Critics of self-regulation, advocates of more regulation

While some stakeholders support European regulation or self-regulation, others clearly favour the use of strict regulation. Opponents of self-regulation, such as consumer protection groups, some NGOs, and policy makers, believe that self-regulation lacks effective enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance and protect the public.

Historically, the call for stricter regulation has focused on issues such as truthfulness, fairness, child protection and the image of women, while ecological concerns are more recent. Recently, the influence of these opponents has grown with increased public awareness of issues such as data privacy, environmental sustainability and corporate responsibility.

Organisations such as BEUC (Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs) are campaigning for stricter legislation at EU level, arguing that self-regulation often does not guarantee fair and transparent practices. Greenpeace, too, is calling for tougher regulation, criticising self-regulation in sectors such as oil and gas for being inadequate in the face of environmental challenges. These groups argue that only binding regulation can ensure adequate accountability and sufficient protection for the public. They argue for supranational regulation to avoid fragmentation of regulatory frameworks and effectively address global challenges.

This preference for regulation over self-regulation raises the question of whether self-regulation is still effective or whether it will gradually be supplanted by stricter rules.

2.5./ Will self-regulation soon be overtaken by regulation?

There are parallel movements between self-regulation and regulation, as ethical rules and the law keep pace with changes in society. Regulation and self-regulation maintain an interdependent relationship in which each can inspire the other.

Self-regulation has sometimes outstripped regulation. Take the example of environmental claims. The ICC Code’s supplementary document (« framework »), developed in 2021-2022, specified the application of the rules on environmental claims, even before the Green Deal directives were put in place. Many self-regulatory bodies have established specific rules for environmental advertising, anticipating future European regulation. For the record, the first ARPP recommendation on ecological arguments in advertising dates back to 1990 (at the time, the BVP).

When an industry implements effective self-regulatory measures, these practices often serve as models for legislation. This is particularly evident in the new digital technologies sector, where the content moderation and data security standards put in place by the sector can inspire regulators when drafting new laws.

Do these convergences pose a problem? Not necessarily, because self-regulation, with its responsiveness, rapid decision-making mechanisms and complaints management, shows what is feasible and effective. In this way, it guides the legislator in drawing up practical and comprehensive rules. This enables the industry to be prepared when the regulations come into force.

Conversely, regulation can sometimes precede self-regulation. Regulation sets minimum standards, encouraging companies to adopt self-regulatory practices to ensure and sometimes exceed compliance. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is an example of this, having prompted companies to strengthen their privacy policies beyond the legal requirements.

The relationship between regulation and self-regulation is therefore symbiotic. In Portugal, for example, the Constitution is integrated into self-regulation. Cooperation with the courts also demonstrates the permeability between hard and soft law. In the UK, the Advertising Standards Authority can refer a case to the Trading Standards Authority or refer a complaint to Ofcom. If the breach goes beyond self-regulation, the Deutscher Werberat may refer the complaint to the relevant authority. Where content or press law issues are involved, the complaint may be forwarded to the German Press Council. In some cases, an appeal may be lodged with the courts.

In Italy, the Court of Cassation considers the violation of the self-regulation code to be an act of unfair competition. This behaviour does not correspond to market standards for healthy competition between operators.

Some of the players we have mentioned are in favour of self-regulation, or even supranational regulation, at European level. So we have to ask ourselves: don’t certain elements seem to demonstrate an incompatibility between the diversity of cultures, the different interpretations and a uniform approach?

3/ (In)compatibility between a uniform approach and cultural diversity?

To highlight the similarities and differences in terms of self-regulation, this third section looks at complaints. What do the volumes tell us? And the grounds? How would the same complaint be handled in different countries?

3.1./ Different volumes of complaints in different countries

The number of complaints is an interesting indicator of the activity of advertising self-regulation. Although the activity of self-regulatory bodies is not limited to dealing with complaints, the latter can reflect Europeans’ perception of advertising and its regulation.

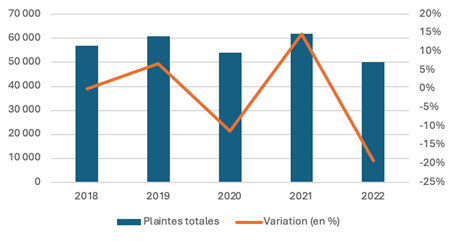

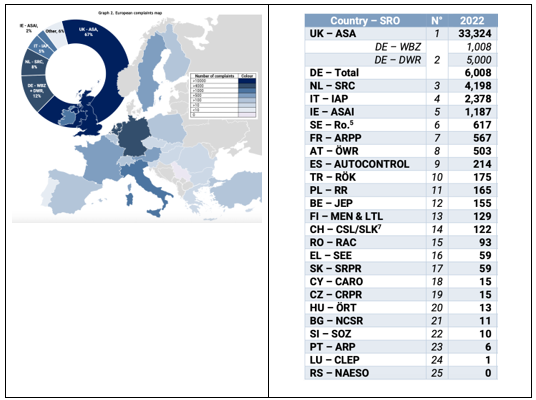

In 2022, the European Advertising Standards Alliance recorded 50,029 complaints about 24,420 advertisements, received by 26 European self-regulatory bodies. The UK and Germany accounted for 79% of all complaints received in Europe.

There is no clear trend in the volume of complaints in Europe. It fluctuates up and down from year to year. This applies both to large bodies, such as the Advertising Standards Authority in the UK, and to smaller bodies, such as the Rada Pre Reklamu in Slovakia or the Reklam Özdenetim Kurulu in Turkey. The volume of complaints tends to evolve irregularly rather than with a stable dynamic over time.

Number of complaints from the 25 EASA countries

On the other hand, there is a significant disparity in the volume of complaints handled by the self-regulatory bodies in the different countries. Of the 26 EASA member bodies in 2022, seven account for more than 95% of complaints between 2018 and 2022. The two bodies receiving the most complaints are those of the United Kingdom and Germany, which together account for 80% of complaints.

Breakdown of complaints by country

Various factors could explain these disparities, as well as the « over-representation » of the UK and Germany in terms of complaints.

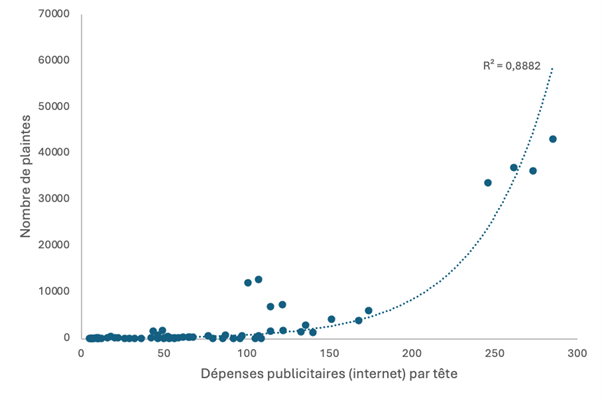

Firstly, the variation in the intensity of advertising activity from one country to another may be an explanatory factor. The intuition is that the more intense the advertising activity in a country, the more it appeals to the public, thus generating more complaints. If we cross-reference the number of complaints with advertising expenditure per capita in the various European countries, we see an exponential relationship between advertising activity and the volume of complaints. One country that escapes this rule is Sweden, where, despite high per capita advertising expenditure, the number of complaints remains low.

Correlation between the volume of complaints and advertising intensity

Other hypotheses may help to understand the high number of complaints in the UK:

- In the UK, the ASA’s decisions are published every Wednesday and picked up by the media. This may be one of the objectives sought by complainants, whether consumers or competitors: to discredit the offending advertiser. In Sweden, the media can also relay the jury’s decisions.

- For a long time, the ASA logo and the words « If you have a problem, call us » were displayed alongside advertisements in the press. In France, the logo of the BVP (the forerunner of the ARPP) has long been present on the mastheads of press titles, even if its visibility is relative.

- The reputation of the SIA, i.e. the recognition of the self-regulatory authorities by the general public, is said to have an influence on the number of complaints.

More generally, the propensity to complain varies from one country to another. The number of complaints per country may be influenced by its history and culture.

Historically, in the Anglo-Saxon countries over the last two centuries, when a problem arose, residents were encouraged to write to their MPs and the authorities; today the connection is still very direct between the British citizen and the MPs. This direct link to the decision-making centre can no doubt be transposed to the ASA. In addition, consumers could be encouraged to take responsibility and lodge a complaint when they feel it is necessary. The French, on the other hand, tend to complain, but without going so far as to lodge an official complaint. Another explanation is the influence of British common law culture, which is based on case law rather than statute law. This makes it easier for the British to resort to self-regulation to create a precedent. In France, and more broadly in Europe, civil law precedes the call to order: there is a greater tendency to resort to hard law than to case law (which may also explain some of the mistrust in self-regulation).

In the countries of Eastern Europe, when self-regulation systems were introduced more recently, the number of complaints was low, because citizens remembered that in the past, complaining could lead to serious repercussions. The historical legacy of centralised control may also have affected confidence in self-regulation. Another hypothesis concerns a possible distrust of political power. Despite a change of regime, after half a century of totalitarianism, the collective conscience could still harbour a degree of mistrust or even a total lack of confidence in the country’s political system. As a result, lodging a complaint with an official institution would rarely be an option. All the more so because the administrative machinery may seem slow, unfair or even corrupt. To a certain extent, this mistrust, justified or not, could be transposed to local self-regulatory bodies.

It could also be assumed that the difference between countries in terms of the number of complaints could be linked to pre- or post-broadcast management (advice before the advertisement is broadcast or not). In France, the low number of complaints could be explained by the work carried out upstream, in particular the pre-broadcast advice and opinion[11] . However, this is also the case in the UK, with Clearcast checking all advertising before it is broadcast on television, Radiowatch doing the same for radio and the Cinema Advertising Association (CAA) for cinema with the Copy Panel, yet the number of complaints is a hundred times higher.

There is no single, universal reason for understanding the volume of complaints in different countries. Rather, it is a combination of factors linked to history, customs, behaviour, markets and everything that makes up the cultural identity of each country.

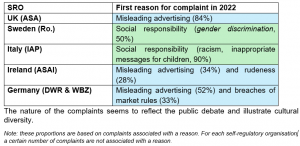

3.2./ Grounds for complaints and national public debates

The first ground for complaint concerns misleading advertising. This point is interesting because it recalls the initial raison d’être of self-regulation in France. The various initiatives that led to the creation of the Office de Contrôle des Annonces (the forerunner of the ARPP), such as « Vérité en Publicité », were designed to « combat misleading advertising and improve the image of advertising in the eyes of the public »[12] .

A century later, the CEP has asked itself whether the regulation of misleading advertising remains the main task of the self-regulatory bodies. In detail, the high proportion of complaints about misleading advertising is explained by the over-representation of the United Kingdom in the volume of complaints. If we look in detail at the reasons given by each body, it becomes clear that each country has its own specific issues and concerns.

Main reasons for complaints

The nature of the complaints seems to reflect the public debate and illustrate cultural diversity.

Environmental issues are very much on the agenda in Italy, Hungary, Germany and Sweden. There is growing public concern about climate change and corporate social responsibility, which has led to an increase in the number of complaints in recent years. Countries such as Germany and the Nordic countries have stricter environmental regulations than those where economic growth is the priority. These doctrinal differences highlight the difficulties of creating unified frameworks that respect different cultural values and priorities.

In the UK, the debate on deconsumerism is alive and well. Campaigning organisations are using the Advertising Standards Authority‘s complaints system to denounce the role they believe advertising is playing in the climate emergency.

Body image in advertising is the subject of debate in Sweden. There has been an increase in complaints about the clothing industry and its social responsibility in the representation of various body images. On the other hand, complaints of discrimination on the grounds of sex have decreased in recent years. Stereotypes are less prevalent, which is reflected in advertising that is more in line with current standards, a subject that Swedish self-regulation has addressed. The drop in the volume of complaints could indicate that self-regulation is working and that advertisers are adapting. But it could also indicate that criticism of advertising and self-regulation is becoming more radical, with people abandoning their complaints to the self-regulatory bodies, believing that they are not doing their job sufficiently. In this case, the drop in the volume of complaints could indicate a lack of confidence in self-regulation.

When the « Black Lives Matter » movement began in the United States, the Deutscher Werberat received numerous complaints about racism in advertising.

In Portugal, societal debates tend to take place first within civil society before being taken over by self-regulation, which deals with complaints. This leads to a certain dissonance between socially hot topics and the subjects of paralegal or judicial decisions.

With regard to the public debate, the CEP has questioned the shift from regulation based on public health (sweet/savoury, tobacco, alcohol, etc.) to the standardisation of lifestyles around an environmental scheme perceived by some as potentially excessive (banning air travel of less than two hours, fossil fuels, encouraging people to stop driving, etc.). The CEP has also looked at societal pressure for advertising to be more politically correct (see CEP Alert « Empathy, bien-pensance, conformism: where is advertising heading? » ).[13]

The environment is at the heart of public debate. In Sweden, flying is frowned upon, while in Belgium, « the car is king ». Some countries are taking a clear-cut stance and encouraging regulation on these issues. As mentioned above, some municipalities go so far as to prohibit the promotion of certain behaviours, such as Edinburgh, which is going to ban advertising for airlines or internal combustion engine cars. However, the French position, which encourages the portrayal of environmentally-friendly behaviour, is not in the majority. Overall, without being able to prove it, it would seem that these pressures are less strong at European level than in France. Other issues are more prevalent than encouraging respect for the environment in other countries.

It would seem that the trend towards a certain conformism in advertising, which the CEP is observing in France, is not affecting other European markets to the same extent. On the other hand, advertising is increasingly seen by some as a legitimate battleground in the ‘culture wars’. In the UK in particular, issues such as body diversity, gender and the rights of transgender people are gaining ground. Advertisements that question these representations often lead to complaints or comments in the media, which can be supportive or critical. In Hungary, the cultural battle focuses on the protection of children and the family. The law on consumer protection considers family representation to be an aggravating circumstance in the case of misleading advertising, and the law on advertising prohibits the promotion of homosexuality.

This openness to public debate enables advertisers to adapt quickly to changes in society.

Google report on blocked ads online

On the internet, the sheer volume of advertising makes it difficult to provide copy advice or report complaints. To combat non-compliant advertising, the major digital advertising networks are automating the regulation of messages broadcast on their channels. Advertising networks such as Google’s algorithmically detect and regulate ads that contravene the company’s standards. Alongside self-regulation, a colossal amount of non-compliant advertising is removed by artificial intelligence. In its Ads Safety Report, Google provides figures to illustrate the scale of this phenomenon.

In 2023, on its advertising network alone, Google removed 5.5 billion advertisements that contravened the rules of use of its[18] advertising network: scams, misleading ads, violation of brand rights, etc. At the same time, 6.5 billion messages saw their audience reduced. Google’s algorithms prevent advertising in certain sectors such as financial products, gambling or adult content from reaching an « inappropriate » target. In total, 12 billion messages were regulated by Google’s algorithms in 2023.

During the CEP hearing, Google explained that its algorithms are calibrated to apply standards developed on a ‘global’ scale. While some of these standards may vary from one region to another – as in the case of pharmaceutical advertising – they are not intended to enforce the rules established by self-regulation in each country. Google refers its advertisers to the various codes established by self-regulation .[19]

In short, the moderation of online advertising by algorithms is less a substitute than a complement to self-regulation. Artificial intelligence makes it possible to examine a volume of advertising that would otherwise fly under the radar. In this respect, each self-regulatory body can put in place its own algorithms to detect advertising that does not comply with the self-regulatory standards, such as the ARPP in France .[20]

3.3./ Convergence and divergence on complaints

Because of cultural differences, advertising that is acceptable in one country may not be acceptable in another, and vice versa. This may lead to the conclusion that Europeans have variable geometry standards, or at least an acceptance of standards that varies from country to country. The media, in particular, are increasingly given the role of referee for the campaigns that their clients entrust to them. They may accept campaigns in some countries and refuse them in others, even if the advertisements comply with the regulations in force in both cases. The complexity lies in the fact that this arbitration is no longer based solely on established rules, but is also influenced by cultural factors. The decision to broadcast an advertisement is often linked to the perception that it could be offensive to certain people or to the fact that the product concerned, although legal, is controversial for societal, moral or community reasons. This seems to be linked to a public tendency to criticise advertising that respects the legal framework but is contested on the basis of broader values. Social networks regularly amplify these criticisms, calling for or demanding self-regulation by the profession. For example, an ad featuring a veiled woman might not provoke controversy in the UK, whereas it could be controversial in France. Another example concerns an international ‘ultra fast fashion‘ brand: a media outlet may wonder whether it agrees to promote it, not for legal reasons, but because of concerns about the sustainability of the products and the responsibility of the company’s business model. Some European subsidiaries may ask themselves this question, while others may not.

To deepen its reflection and identify points of convergence and divergence in the interpretation of ethical rules, the CEP sought the « informal » opinion of six European self-regulatory bodies on four complaints handled by the Jury de Déontologie Publicitaire in France. The bodies consulted were the Advertising Standards Authority in the United Kingdom, Auto Regulação Publicitária in Portugal, Deutscher Werberat in Germany, Istituto dell’Autodisciplina Pubblicitaria in Italy, Önszabályozó Reklám Testület in Hungary and Reklamombudsmannen in Sweden. The aim here is not to ‘judge’ or pass value judgement on the opinions of the various juries, but to understand whether or not the interpretation of the codes and recommendations of the self-regulatory authorities is convergent.

Complaint number 1 – Nudity

The complaint concerned an outdoor poster featuring a photo of a completely naked man lying on his stomach beside a swimming pool, promoting an offer of male striptease in a cabaret.

The UK jury found that the nudity was not sexually explicit, as the genitals and buttocks were not fully visible, the facial expression was not sexually suggestive, and the ad did not contain overtly sexual lingerie or accessories associated with sexual activity. In addition, a certain degree of nudity is common at poolside. As the advertisement relates to a male striptease show, the nudity is relevant to the service being advertised and is not gratuitous. The advertisement would not be considered degrading or exploitative and would not objectify men by using their physical characteristics to draw attention to an unrelated product. However, a restriction on placement should be applied.

The Portuguese jury considered that the advertisement was likely to offend the standards of decency prevailing in the legal system. It would also consider that the medium used does not allow for the restriction of the times and/or the age segmentation of the public, thus allowing it to be viewed by anyone, which does not respect the limits imposed by the age classification of the activity. The jury would therefore find the complaint well-founded.

The German jury considered that the man’s position did not express excessive nudity: he was not posing erotically and the overall situation did not encourage him to reveal his sexuality. As a result, the advertisement would not be deemed not to comply with the Self-Regulation Code.

The Italian jury would not consider that the image of a naked man, showing no intimate part of his body, could be perceived as vulgar or indecent. It would not see it as exploiting a gender stereotype, or as a form of discrimination. A male striptease show is a legitimate activity, the advertising of which is consistent with its nature. Consequently, the advertising would not be deemed contrary to the Code.

The Hungarian jury considered that the depiction of the man was not disrespectful and that the nudity was acceptable, as it was linked to the male striptease service. As the depiction of the man does not express vulnerability or subordination, the image would not be considered disrespectful or unacceptable. However, as indicated by the UK jury, a restriction would be necessary due to the strip-tease advertisement and the full nudity of the model, to ensure that children under the age of 18 could not see the advertisement. Apart from this restriction on the media carrying the advertisement, the Hungarian jury would consider the complaint unfounded and reject it.

The Swedish jury would invoke freedom of expression and consider that the complaint did not fall within the scope of the ICC Code. As mentioned in paragraph 1.1, Sweden applies the ICC Code directly without any specific adaptation.

The French Jury ruled that this depiction was « likely to offend the sensibilities, shock or even provoke the public by propagating an image of the human person that offends his or her dignity and decency« , especially as it was being displayed on the public highway. He emphasised the instrumentalisation of the human body by reducing it to the function of an object, in this case a sexual object. As a result, the complaint was declared well-founded.

Complaint number 2 – Misleading consumers about production conditions

The complaint concerns a restaurant chain’s advertisement showing a chicken bouncing on the belly of a cow lying on its back, legs in the air, in the middle of a herd grazing in a meadow. The complainant’s main complaint was that the natural setting depicted was misleading and did not reflect the actual conditions in which the chickens were reared.

The UK jury would consider the ad to be somewhat surreal and would see it as humorous. They would find that the ad contained no direct or implied environmental or animal welfare claims, especially given its comic and surreal tone. Consequently, there would be no breach of the Code.

The Portuguese jury considered that the advertisement was hyperbole, perceived as such, and should not be considered misleading. The average consumer would not be likely to be misled. They would consider that the advertisement did not provide any information about the way in which the chickens were reared, as it contained no implicit or explicit reference to this. Consequently, there would be no breach of the Code.

The German jury also considered that the consumer understands that the advert is humorous and does not depict the conditions under which chickens are reared. Consequently, there would be no breach of the Code.

The Italian jury did not see any claims relating to the animal welfare or environmental quality of the advertised product. Consequently, it would consider that the advertising did not contravene the Code.

For the Hungarian jury, the scene should not be taken literally, and the consumer would understand this perfectly well. Although the ad could be criticised for making fun of animals, the absurd and humorous nature of the ad would mitigate against this. Like the German jury, the Hungarian jury would consider that the advertisement did not concern the way in which chickens were reared. Consequently, there would be no breach of the Code.

The Swedish jury would also consider that there was no deception due to the humour. It would consider that the average consumer probably knows that chickens are not always reared in the wild.

The French Jury ruled that the advertisement was likely to mislead the consumer and thus infringed the principles of fairness and truthfulness set out in the ICC Code, due to the significant discrepancy between the representation of the chicken and the reality of the farming conditions, as well as the particular sensitivity of the public to this issue.

Complaint number 3

The complaint concerns an advertisement posted on Facebook showing a stationary vehicle in a fictitious setting, accompanied by texts such as « {name of vehicle} passes and you step aside, {name of vehicle} dominates and you bow ». These texts refer to a sequence from a television programme that has gone viral on social networks: « Marina passe et tu t’écartes, Marina domine et tu t’inclines ». The complainant accused the ad of encouraging drivers to feel like « kings of the road » and to show no respect for other road users.

The British jury felt that the texts may allude to domination, but that readers are unlikely to understand them as literal instructions promoting an aggressive or irresponsible style of conduct. The text is accompanied by a lipstick emoji and a hash word, which would indicate a lighter tone. Consumers could therefore understand or deduce that the text is a comic retort or a reference to a meme. As a result, there would be no breach of the code.

The Portuguese jury could consider that the texts could be interpreted as an expression of superiority and a potentially aggressive attitude on the part of the vehicle driver. They could also be perceived as offensive or potentially contrary to human dignity if they suggest the subjugation of other people in the context of traffic, making the advertising disrespectful and therefore contrary to human dignity. However, the Jury did not consider that these texts had the effect of influencing aggressive or negative behaviour in traffic, as the advertising slogans could be interpreted metaphorically. Consequently, the complaint would be rejected.

The German jury considered that the text encouraged aggressive and anti-social behaviour, which would constitute a breach of the General Code. The jury would consider that the reference to the sequence in the TV programme was not sufficiently obvious to consumers; if the reference were clear, the assessment would be different and in favour of the advertiser.

The Italian jury would judge that the expressions used do not refer to precise characteristics of the vehicle and do not explicitly mention its power or speed. Ultimately, they could be seen as an expression of bravado and arrogance, and are not associated with images of the car in active driving or on the road. The commercial would not therefore offer an explicit model of driving to be imitated, nor would it present elements that suggest particularly fast, reckless or imprudent driving, or that could incite the addressees to behave in such a way as to expose them to risky situations, in disregard of the rules of prudence and responsibility that are essential when driving vehicles. Consequently, there would be no breach of the Code.

The Hungarian jury would consider that the wording « exceeds » refers to driving, encouraging fast and aggressive driving, i.e. dangerous driving behaviour, and is therefore unacceptable. The complaint would be considered well-founded.

The Swedish jury would consider that consumers in general probably perceive the advertising as likely to encourage inappropriate or dangerous driving.

The French Jury found that the advertisement conveyed the idea of a hierarchy and a balance of power, which took on a particular meaning in the case of a motor vehicle. Even in a humorous tone, it lent credence to the idea that the driver of this vehicle could dominate the road, which is incompatible with the highway code and the requirement for respectful driving. The jury considered that the advertisement in question failed to comply with ethical provisions.

Complaint number 4

The complaint concerns an advertising video for a range of cat food, in which images of cats and products are accompanied by the following texts: « Finally, healthy food for your cat that is eco-responsible and has an impeccable composition », « the healthiest and tastiest cat food in the world », « to avoid digestive problems, vomiting, diarrhoea and chronic illnesses », « better digestion », « no digestive problems », « less smelly stools ». The complainant considers that the expression « the healthiest and tastiest cat food in the world » should be put into perspective, that testimonials do not demonstrate beneficial health properties, and that the claim « the best food for growth » is made without comparative evidence.

The UK jury would consider that there had been a breach of the advertising codes. However, if the advertiser had responded immediately by making changes to the advertisement, the jury would probably have given advice rather than pursuing the matter as part of a formal investigation. In a formal investigation, the jury would ask the advertiser to provide strong documentary evidence that its product is healthier than any competing brand. It would also contact the Veterinary Medicines Directorate, the UK government health regulator that oversees the regulation of veterinary medicines, to determine whether the claims were medical or whether the product contained elements that could confer a medical effect. If the advertising claims were not classified as medicinal, the jury would require the advertiser to provide evidence to support its claims. The jury would find it highly unlikely that the advertiser would have appropriate evidence for general claims and would advise the advertiser to use a more specific claim and explain what it means in the advertisement.

The Portuguese jury felt that superlative claims such as « the healthiest and tastiest cat food in the world », without concrete evidence, are likely to mislead by unjustified exaggeration. Claims must be based on verifiable evidence, and any health claim (even animal health claims) must be supported by valid scientific studies accepted by the scientific community. Claims of health benefits such as « better digestion », « no digestive problems », « less smelly stools », which are not scientifically validated, would constitute misleading advertising and could not be replaced by feedback or testimonials from customers showing satisfaction or improvement in the health of their cats. As a result, the Code would not be respected.

The German jury considers that the subject falls within the scope of legal regulation, through the Lebensmittel, Bedarfsgegenstände und Futtermittelgesetzbuch (Food and Feed Code), and not self-regulation. The Wettbewerbszentrale (competition centre) would be more appropriate to deal with this complaint. He points out that the LFGB does not authorise the advertising of animal feed premixes with the promise of preventing diseases that are not the result of poor nutrition.

The Italian jury found that these claims were not contextualised, relativised or supported by scientific studies to establish the prevalence and superior qualities of the product compared to similar products; testimonials could not be relied upon for this purpose. He considered that the average consumer would be misled by the wording of the message. Consequently, there would be a breach of the Code.

The Hungarian jury would consider that the allegations are only acceptable if they are justified in accordance with industry standards, which is not the case here. It would consider the complaint to be well-founded.

The Swedish jury would find that the claims that cat food is the best and healthiest in the world are vague and non-specific. Therefore, if the advertiser could not substantiate its claims, the complaint would be upheld.

The French Jury noted that the messages in question were neither relativised nor contextualised; the sole reference to a list of traditional ingredients making up the product could not take the place of a reference when it was not supported by any scientific work. In addition, he felt that the vocabulary used to describe the food as « the healthiest and tastiest in the world » had no basis in fact. Furthermore, the functional claims were not accompanied by any justification, proof or scientific demonstration. Consequently, the Jury is of the opinion that these advertisements fail to comply with the aforementioned ethical rules.

The study of these complaints by juries in different countries shows that, even if self-regulatory frameworks are based on the same principles, interpretations vary according to a country’s relationship to culture, humour and sensitivity to certain subjects.

4./ Conclusion and recommendations

« In varietate concordia »[14] , the motto of the European Union, could also be applied to advertising self-regulatory bodies in Europe.

The common principles of « lawful, truthful, honest and decent advertising » promoted by the ICC Code are complemented by national specificities shaped by the political history, cultural heritage and social and economic context of each country. Self-regulatory bodies have the capacity to perceive and analyse cultural particularities as well as societal trends. As such, they can be seen as capable of providing responses tailored to the realities and singularities of the society in which they operate.

The exchange of ‘best practice’, notably through the European Advertising Standards Alliance, is helping to raise standards and requirements across Europe.

However, the CEP’s investigations highlight the contradiction that exists between, on the one hand, the desire for uniformity expressed by some, and, on the other, the undeniable variety of representations, cultures, and therefore of the orientation of public debates. What is discussed in France is not necessarily debated elsewhere. For example, the existence of anti-advertising activism and the importance of environmental issues vary from one European country to another.

The desire for international standardisation expressed by some is therefore in clear conflict with the heterogeneity of national contexts and the need to respect cultural diversity. Consequently, the CEP does not recommend the establishment of a pan-European self-regulatory body.

On the contrary, this diversity has the advantage of forcing the advocates of European regulation, the major technology platforms and certain large international advertisers, to adapt to local cultures. The cultural specificities, societal trends and regulatory landscape of each country require flexibility and adaptation of the advertising message if it is to be acceptable, respectful and effective.

This cultural diversity, reflected in legislation and self-regulation, does not appear to restrict the creativity of international brands. On the contrary, it is likely to respect it, by enabling brands to come closer to national issues and specificities.

In the light of this European comparison, the CEP invites the ARPP to reflect further on :

- Strengthening, if not reinforcing, the dialogue with public authorities, be they European, national or local, so that proposed amendments to texts relating to advertising, the media economy and communication are preceded by impact studies and are subject to reviews once they have been implemented. This recommendation does not ignore the reality of the cohabitation of contradictory logics, and the possibility of a confrontation based on sometimes divergent objectives and agendas, which remain the signature of any democratic functioning.

- Expanding the arsenal of « name and shame » measures, drawing on British and German practices. This could be done by informing the specialised press of the most significant opinions of the Jury de Déontologie Publicitaire, and by forwarding to it once a year a list of advertisers and content creators who have repeatedly failed to comply with the code of ethics, or even failed to respond to requests from the Jury de Déontologie Publicitaire.

The CEP invites the ARPP and all its counterparts operating in the European area to coordinate communication channels for consumers in order to simplify and standardise the procedure for lodging complaints with juries.

Furthermore, the original principle of self-regulation in France is the negotiation and cohabitation of three logics: those of the advertisers, the agencies and the media. Everyone knows that they have their own interests and their own visions. However, the CEP would point out that self-regulation is not a matter of professionals sitting down together. Self-regulation is a discipline freely agreed upon to ensure that advertising is « honest, transparent and responsible ».

It is not opposed to hard law, but complements it. To increase the credibility and visibility of this self-regulation, it is important to :

- Make the most of existing and sometimes contradictory discussions with the administrative authorities.

- Improving dialogue between consumers, associations and NGOs and the Jury de déontologie Publicitaire (JDP) outside the handling of complaints

- Publicise self-regulation, to explain in the public debate that it guarantees flexibility and responsiveness, and therefore effectiveness. Occasionally point out that self-regulation only judges the content of advertising. In the context of a single European market, banning a product and/or advertising for a product is a matter for the law.

For its part, the CEP notes the usefulness of this system of self-regulation: the ARPP’s various barometers and studies reveal a high percentage of advertising compliance. This is borne out by the 93.6% compliance rate with the « Sustainable Development » recommendation in the twelfth « Advertising and the Environment » report produced by ARPP and ADEME on environment-related advertising broadcast at the end of 2023 and the beginning of 2024[15] . Similarly, only three breaches of the « Image and respect for people » recommendation were found out of 13,743 advertisements analysed in the seventeenth « Advertising & image and respect for people » report published in 2023 . [16]

Bibliography

- GALA Advertising Law Book – Third edition (2024)

- Private Regulation and Enforcement in the EU, Finding the Right Balance from a Citizen’s Perspective, edited by Madeleine de Cock Buning and Linda Senden, chapter « Trust through Responsibility: Advertising and Self-Regulation in Europe » by Oliver Gray.

- European trends in advertising complaints, copy advice and pre-clearance 2022, European Advertising Standards Alliance[17]

- Vive l’incommunication. La victoire de l’Europe, by Dominique Wolton, published by François Bourin, 2020.

- Jacques Delors. L’unité d’un homme, by Dominique Wolton, Odile Jacob, 1994

Interviews with Dominique Wolton. - La dernière utopie. Naissance de l’Europe démocratique, by Dominique Wolton, Flammarion, 1993.

- Revue Hermès N°93: Northern Europe, so near, so far, September 2024

- Revue Hermès N°90: Europe between incommunications and wars, October 2022

- Revue Hermès N°77: Les incommunications européennes, May 2017

This opinion, supervised by Albert ASSERAF, Brice MANGOU, Rémi DEVAUX, accompanied by Lucas BOUDET and Tudor M. MANDA of the European Advertising Standards Alliance, coordinated and co-written by Bertrand ESPITALIER, summarises the reflections of the Advertising Standards Council, whose members and experts are : Its members and experts are: Dominique WOLTON, Christine ALBANEL, François d’AUBERT, Pascale MARIE, Zysla BELLIAT, Benoit LE BLANC, Brice MANGOU, Charles BERLING, Fabienne MARQUET, Albert ASSERAF, Pascal COUVRY, Denis GANCEL, Clémence GOSSET, Thierry LIBAERT, Gérard UNGER, Rémi DEVAUX, Cristina LINDENMEYER, with the participation of Alain GRANGÉ CABANE (Réviseur de la Déontologie Publicitaire).

The following people were interviewed in this context:

- Lucas BOUDET†, Managing Director of the European Advertising Standards Alliance (EASA)

- Caroline BOUVIER, Partner at Bernard-Hertz-Béjot and French representative of the Global Advertising Lawyers Alliance (GALA)

- Tamara DALTROFF, CEO of the European Association of Communications Agencies (EACA)

- Laureline FROSSARD, Director of Public and Legal Affairs, Union des marques

- Oliver GRAY, co-chairman of the working group on the revision of the ICC Code

- Monika MAGYAR, Senior Legal Advisor of the European Association of Communications Agencies (EACA)

- Chiara ODELLI, Head of Industry Relations EMEA at Google

- Ophélie RAIMBAULT-GERAR, associate at Bernard-Hertz-Béjot

- Catherine SEDILLIERE, Advertising Industry Relations Manager, Google France.

[1] Dominique Wolton

[2] « Denken heißt vergleichen », Walther Rathenau, German industrialist, Minister for Reconstruction (May-October 1921), then Minister for Foreign Affairs (February-June 1922) of the Weimar Republic. Berlin 1867-Berlin 1922

[3] Self-regulation refers to the process by which a sector of activity regulates itself, without the direct intervention of the State or an external authority. As for co-regulation, this is a process that combines the efforts of private players and the intervention of public authorities.

[4] Dieudonné Mandelkern (1931-2017), Honorary Section President at the Conseil d’État (Council of State)

[5] https://commission.europa.eu/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en

[6] In 1991, Sir Leon Brittan (1939-2015), then Vice-President of the European Commission and Commissioner for Competition Policy, challenged the advertising industry to find ways of solving the problems raised by the creation of the Single Market through self-regulation, thereby avoiding the need for detailed legislation, which the industry opposed. Later that year, advertising industry representatives from across Europe agreed to give formal, independent status to a hitherto ad hoc group of national self-regulatory bodies (SROs) from a number of European countries, including the BVP in France. The new body, created in 1992, was called the European Advertising Standards Alliance (EASA).

[7] www.jdp-pub.org/statuts-et-ri/#art15

[8] www.arpp.org/influence-responsable/createurs-de-contenus-certifies/

[9] https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/e6cd4328-673c-4e7a-8683-f63ffb2cf648_en?filename=Political%20Guidelines%202024-2029_EN.pdf

[10] Communiqué de l’ARPP le 1er août 2024 : Le Certificat de l’Influence Responsable de l’ARPP devient européen ! www.arpp.org/actualite/certificat-de-influence-responsable-de-arpp-devient-europeen/

[11] Advertisers and advertising agencies can call on the expertise of ARPP’s legal advisors for all media and all forms of commercial communication, at all stages of the creative process.

Before advertising spots are broadcast on television or on-demand audiovisual media services, they must be submitted to the ARPP and receive a « favourable opinion ». To issue this opinion, the ARPP checks that the advert complies with legal and ethical provisions.

[12] Martin, Marc (2016). History of advertising in France. Presses universitaires de Paris Nanterre

[13] www.cep-pub.org/actualite/alerte-1/

[14] « United in diversity

[15] www.arpp.org/actualite/categorie/bilans-et-observatoires/publicite-et-environnement/

[16] www.arpp.org/actualite/publicite-et-image-et-respect-de-la-personne-2023/

[17] www.easa-alliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/2022-European-Trends-in-Advertising-Complaints-Copy-Advice-and-Pre-Clearance.pdf

[18] Google Global Ads Safety Report 2023

[19] Google Ads, List of advertising sector codes. https://support.google.com/adspolicy/answer/11108174

[20] ARPP, Avec » Invenio « , l’ARPP franchit une nouvelle étape issue de sa R&D dans l’accompagnement déontologique de la publicité digitale, 11 June 2020.